Depth and Complexity

The Depth and Complexity Framework is a thinking-based differentiation tool.

It is a conceptual ‘toolbox’ that prompts students to think in abstract, high level ways similar to disciplinarians.

It was developed by Dr. Sandra Kaplan and Betty Gould. They sought to increase rigor into the general curriculum by asking students to develop scholarly behaviours, consider knowledge through the perspective of career specialties, or disciplinarians and to use a variety of critical thinking skills.

The Depth and Complexity Icons are visual prompts designed to help students go beyond surface level understanding of a concept and enhance their ability to think critically. These critical thinking tools help students dig deeper into a concept (depth) and understand that concept with greater complexity.’

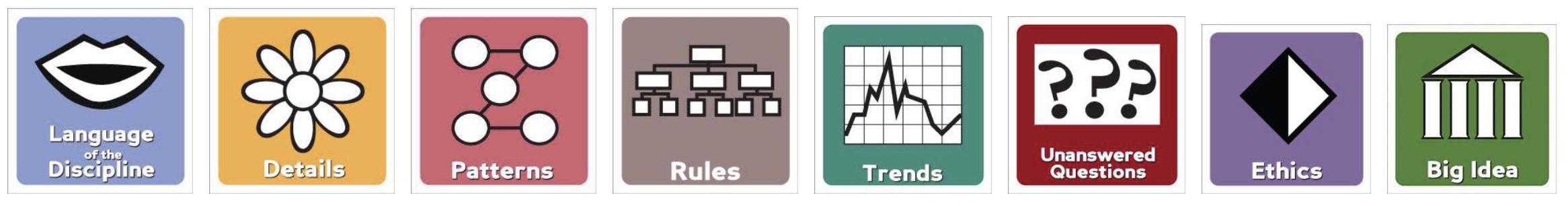

The Depth and Complexity Icons

They are arranged in order of depth from the concrete to the abstract, and complexity from concepts and ideas to a more sophisticated level to connect learning across multiple subject areas.

However, the icons do not need to be taught in a certain order, all at once, or within specific lessons. The icons should be thought of as a lens of learning that will activate learning of content using higher-level thinking skills.

The prompts of Depth and Complexity challenge learners of all ages and are applicable to every subject.

Elements of depth

Elements of complexity

Content Imperatives

The Content Imperative icons represent a set of terms that activate higher levels of knowing. These icons focus the investigation of a topic of study from a broad, general area to a more structured and specific one. Content Imperatives can be effective when used independently, but they were designed to be used in pairings with the Depth and Complexity Icons. Content imperatives are introduced from Year 5 onwards.

Universal Theme

A universal theme is an organizing concept that transcends time and place, and brings focus to learning across subject areas.

- provides a scaffolding or organizing system to classify information from various disciplines.

- facilitates greater retention of subject matter as students make connections within, among, and across the disciplines.

- necessitates the use of critical and creative thinking, problem-solving, and research skills in an integrated and contextual manner.

- affords students opportunities to examine the areas of similarities and differences in the structure and topics of the disciplines.

Universal themes are supported by ‘big ideas’ (generalisations) that teachers and students develop together through the use of a variety of immersion activities at the beginning of Term one. The big ideas help break down the universal theme into understandable generalisations the students and teachers can work with throughout the year. Here is an example of a universal theme and the corresponding big ideas.

Universal theme: Change

Big ideas

Change can be positive or negative

Change has cause and effect

Change occurs over time

Scholarly Habits

Dr. Sandra Kaplan developed a set of characteristics or behaviours most common in “scholars” while conducting research with gifted and talented students.

These are traits that students are taught, particularly in years 5-8, to exhibit through modelling, guided practice, and ongoing reinforcement.

Behaviours include pondering ideas, intellectual risk-taking, preparation, excellence, academic humility, curiosity, saving ideas, multiple perspectives, perseverance, varied resources, and goal setting.

Thinking Like a Disciplinarian

Students examine content through the lens of a specific disciplinarian. This engages students in the use of academic vocabulary and specific content knowledge. It becomes a tool for differentiation, research, and interest-based exploration. Disciplinarians can be broad, specific, or in between.

An example of this is when students are working in science, they discuss and look at how a scientist thinks, acts in their work, what specific language they would use, and what are the ways in which they operate scientifically.

For example, scientists make observations, they ask questions, they make hypotheses based on what they know, they experiment, and they report and analyse their results.

Using the Depth and Complexity tools allows teachers at Sts Peter and Paul school to strengthen their capability in delivering differentiated learning that links to our school vision.

‘Our vision is to nurture independent learners who are creative, critical and caring in their thinking, strengthened by their Catholic identity.’

The tools allow all students to develop age-appropriate critical thinking skills at the cognitive level of the individual child while also allowing students who are gifted to be extended and challenged throughout the classroom learning programme.

Further reading

Center for Depth and Complexity under the ‘Learn’ tab on this website you can find more information about universal themes and thinking like a disciplinarian.

Tips for Parents

Tips to help you encourage your child to think with depth and complexity.

(Adapted from an article by P. Wilkes Davidson, Institute for talent development, USA 2014)

“Everyone thinks. But not everyone thinks equally well.”

The brain is a pattern maker, and the majority of the time, those patterns help us navigate the world in a highly efficient manner. However, sometimes those patterns lead us astray and prevent us from looking deeper.

Depth and complexity tools are a way of providing a broader set of lenses through which to look at what they read and their studies in Mathematics, Social Studies, Science, Technology, Religion, etc.

There are eleven tools: eight encourage deeper thinking and three encourage more complex thinking.

Language of the discipline

This refers to words that are significant to a particular discipline (think area of learning).

This includes subject-specific vocabulary, jargon, tools, signs, and symbols, etc.

With books, it can be author, illustrator, title, cover, etc.

Mathematics may include addition, subtraction, addend, equals, numerals, denominator, etc.

Details

This is an area you can model by asking your child to pull out the important details of what they have read rather than telling the story completely.

You can help further in this area by broadening your child’s ability to be aware, creative, and intuitive so they are using their sight, hearing, taste, smell, feel, imagination, as you discuss anything where you interact with them, such as on car trips, at the supermarket, out for a walk, baking, tidying, etc.

Patterns

Our brains are natural pattern makers, and we can encourage our child to notice and use those patterns effectively. You might ask such questions as:

What did you notice about ________ that you’ve noticed somewhere before?

Based on the pattern you noticed, what do you predict will happen next?

Describe the pattern you noticed.

What does this pattern remind you of?

Was there anything about this pattern that surprised you?

What are the key elements of this pattern?

What might have caused this pattern?

What name might you give this pattern?

How could we stop this pattern from recurring ?

Rules

This is a dimension that children learn early on as they navigate the world and hear the word NO when they do not follow a rule.

We need to expand the notion of rules with children so they see the rules we follow in every area of learning, including Mathematics, Writing, Reading, Science, Sport, etc., and the different cultural rules that may exist in their home, school, society, New Zealand, as well as internationally.

This can expand to the rules we follow on the road when driving a car or riding a bike, etc., and why we need them. It also includes any rules that we follow in our daily lives and why we have them.

Trends

There are many ways to nurture awareness of trends. You might highlight the styles of clothing, transportation, technology, takeaway foods, or anything else that may relate to what they are studying or reading. Talking to grandparents about when they were young or looking at old photographs can show how things have changed for them and for you. You might even share what sort of books you read and what TV programmes you watched so they can see what trends have developed.

Unanswered questions

Some children think they need to know everything about a topic they are studying. We need to be sure to let them know that they may have questions that cannot be answered, and that this is okay. Many experts spend their lives looking for answers to questions they have.

It is important that they are able to ask good questions, and then you can help them find the answer (not answer it for them). Maybe say, ” What a great question! I wonder how we could find out the answer if there is one?”

Do be aware that they may have questions to which you cannot find an answer easily, and this could lead to more questions and more finding out!

Ethics

It is important that we help children identify and analyze ethical issues. These can be found in stories they read and in almost any subject they study. They may be issues seen in the news or experienced in interactions with their peers.

As they grow, they stimulate thinking about ethical issues by highlighting prejudices, propaganda, controversies, that are age-appropriate. For your young children, you may want to focus on Bible stories or their early books and examine the behaviour of people.

Big ideas

Being able to identify themes, laws, and theories is an important skill for children to learn. One issue is the ability to summarise main ideas. This is not retelling ; rather, it involves looking for the purpose of a book, story, etc., or understanding the main idea that is the basis for a scientific belief, or identifying one main idea we can learn from a Social Studies topic.

The more complex tools are:

Over time

As you read a story with your child, you might look at how the characters, problems, settings, or other aspects of the story change from the beginning to the end. Being able to relate across time is a far more complex way of thinking than just looking at how things are now.

Relating over time helps your child develop a deeper understanding of the historical influence of events , as well as the implications of current innovations-cell phones and the internet, plus AI might feature.

Discussion with grandparents, looking at photographs, talking about the family tree, sharing your memories of what life was like when you were young, and looking at how and what things have changed.

Multiple perspectives

We need to help our children see things from another perspective, whether that be in a visual – spatial way or in understanding how other people view the same topic or idea. Parents need to be models of restraint when discussing important and polarising issues such as politics and international affairs, and help their child see issues from a variety of perspectives and how others may think and feel. Bible stories are a way to start, or the books your child is reading.

Across disciplines

Although learning areas at school may be separate, true learning is often multidisciplinary. This is another way your child can gain a more complex understanding of what they are reading and the information they are learning. When you are out with your child or just talking at home, you can raise how different disciplines are involved in such things as choosing a new appliance (designer, manufacturer, people making the materials to be used, etc.), building a house (architect, carpenter, electrician, paver, town planner, etc.), mending the road (traffic management, council, road workers, etc.), shopping (shelf stacker, merchandiser, salesperson, checkout person, designer of cash registers, scanners , etc.).

A way to get started – Use “I wonder” questions.

This may get your child thinking in a way that doesn’t seem like you are asking lots of questions.

For example, in the supermarket: “I wonder why this product is in a bottle, but this one of the same thing is in a carton,” or “I wonder why this brand of the product costs… but this one costs only…?”

“I wonder why the author called this book….”

“I wonder why they chose to put this picture on the front of the book.”

“I wonder which is the quickest or shortest way to get to school and why.”

“I wonder what would happen if we put a cup of flour in this recipe rather than three-quarters of a cup.”

“I wonder what will happen next in (the TV programme) and why?”

“I wonder what it would be like to be an animal (specific animal)?”

“I wonder who invented weekdays and weekends, and why?”

Always keep in mind how you might find out and why.